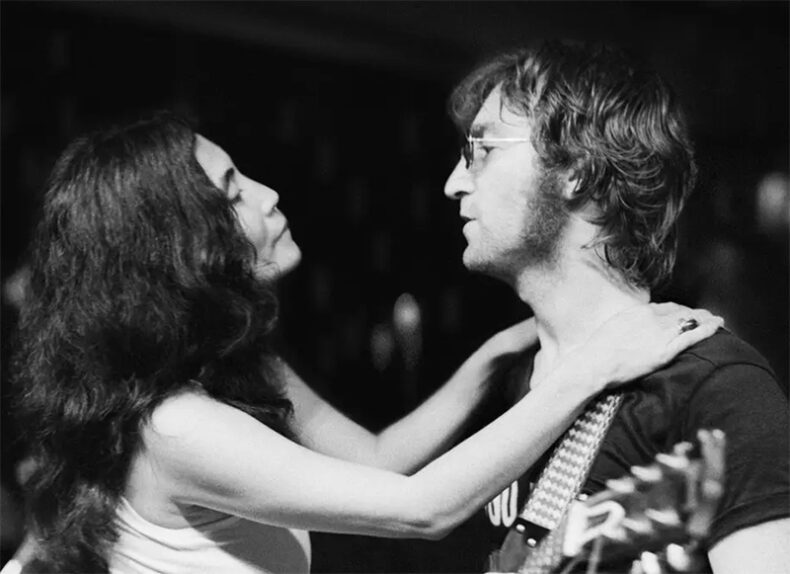

THE TASK OF MAKING A FILM THAT JOHN AND YOKO WOULD APPROVE OF

A CONVERSATION WITH DIRECTOR SAM RICE-EDWARDS

2025 seems to be a banner year for John Lennon and Yoko Ono documentaries. Three have been released, each covering a very specific time in Lennon and Ono’s career. One To One: John & Yoko is a remarkable documentary due to excite John Lennon, Yoko Ono, or Beatle fans. The film’s two directors, Sam Rice-Edwards and Kevin Macdonald have created a truly original film exploring 18 months of John and Yoko’s life in New York City in 1972, culminating in two concerts on August 30, 1972, known as the One To One Concerts.

There were two shows, one was in the afternoon, and one in the evening at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Lennon and Ono organized the event, which included many famous guests, such as Roberta Flack, Stevie Wonder and Sha Na Na. Not only was the concert a good cause (all the money went to help the children at the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island), but they were the only complete concerts Lennon ever performed in his career. He had performed live several times, but in short sets in larger festivals/rallies. Here Lennon (and Ono with The Plastic Ono Band and Elephant’s Memory) performed a complete concert.

“The film came about, the seed for the whole thing, was the fact that there was this concert footage that existed and audio. It was just sitting somewhere, but people knew that it had never really been done its true justice. And it was the only full concert that John did after leaving The Beatles. It had an inherent cultural value, and I think people knew that something had to be done. I don’t know everything from the beginning, because it was before my time, but ultimately, Peter Worsley, the producer of the film, got involved and he was looking for the right person to contextualize this concert and come up with something to do with it. Kevin Macdonald got involved, and Kevin called me up and said, ‘do you want to come and make a film about John Lennon and Yoko Ono?’ And he also said ‘I don’t really want to do a rehash of a number of films that are out there about The Beatles. We want to do something fresh.’ It was one of those phone calls when you just can’t say no.”

The film does not just focus on the concert, but Lennon and Ono’s time while they lived on Bank Street in Greenwich Village. “The mark of a good film is if you get to really know the protagonist and see the change they go through and learn something from it. We wanted to do something where you really got to know John Lennon and Yoko Ono in a deeper way instead of a story about the concert. The story of the concert became the culmination of the 18 months they went through. We felt a lot had happened to them at the time. What we wanted to do, was instead of force a strict narrative on the film, we wanted the film to be an experience where the viewer gets to know John and Yoko in a way that hadn’t been possible before but also to see the world in the way they were seeing it at the time, because that also reflects what they were going through. And again, not forcing a narrative but showing the viewer things that were important to them and giving them a full picture of John Lennon and Yoko and the time they were in.

John Lennon was a fan of television, he had it on in the background at all times. Television is an important structure that is used in the film, allowing the filmmakers to tell the story. “That was something Kevin came up with, when you have a project like this, where you have some amazing footage of a concert, and complete freedom of what to do. Kevin and I sat around thinking we should do this or that, coming up with ideas listening to interviews and reading. One day, Kevin came in and said ‘I think we should tell the story of 1972 through their television’. That was a lot of what they did. They moved into a small apartment and it became a cultural community hub, but a lot of what they did was view the world through their television. So we tried to reflect and when Kevin first proposed the idea to me, I was a bit worried about it. I thought it was quite experimental and quite a brave way to go and there was definite scope for it not working. But I also knew that feeling of fear was a good thing because we were stepping outside of our comfort zone and it had the potential of being a much fresher and exciting film.”

The two directors also had access to previously unheard interviews, phone calls and other recordings in the Lennon/Ono archives. These clips help tell the story as well.

“We went through thousands of hours of archives to choose the bits we have chosen,” said Rice-Edwards. “You had two different areas, the mountains of archives from the time, that maybe weren’t so focused on John and Yoko and really that was watching through hours and hours and finding things instinctively that could be interesting. We would put stuff in the film, then take it out. The stuff you see in the film now stood the test of time and upon reflection are really saying something important. But on the other side, you had very specific kinds of archives, like the telephone calls. We had a call one day from Simon Hilton, who works with Lennon estate. And he had been over in New York at the archive, and in my imagination, was walking around and looking on a dusty shelf. There was a box, not labelled, and he peeked in the box, and there were all these reel to reel tapes, and no one knew what they were until they had a lesson. It turned out to be recordings of telephone calls of John and Yoko’s Bank Street apartment from the exact period we were talking about. We knew they were really unique.”

For Rice-Edwards there was a feeling of responsibility to tell the story and add to the history of the Lennons. “We felt a responsibility to make a film that John and Yoko would approve of. I don’t mean in the content, but stylistically and that it has artistic value in itself. We wanted to add the amazing lineage that John and Yoko have and that was really what was in that initial call from Kevin. The prime thing for him was we needed to make something fresh and exciting.”

Of course, the film has incredible footage of the concert and rehearsals. “We did some cleaning up. It had been remastered, but we kept it pure. We went back to the source. It is funny with the concert footage; it was such a mixed bag. The story goes that the people on the cameras were actually very high at the event. So, a lot of the camera work was really questionable. Some strange decisions like people leaving it out of focus for a long time. It did provide a challenge, but it was shot on film, they exposed it right, and you have John and Yoko really giving a performance of a lifetime. Those things click together to make it something really special. The way we dealt with the concert footage, but we decided to have a very long shot, not a classic concert edit where it is cutting all over the place. We wanted the viewer to have the feeling that they were at the concert and they can connect emotionally to John and Yoko. So, we would leave a close-up on them for a long, long time, and we felt this was more effective than doing a punchy, cutty edit.”

The film is complete and ready for theatregoers. Rice-Edwards hopes that people walk away from the film with a few thoughts and ideas. “I hope they get to know John and Yoko in a deeper connected way than they have previously, because I think it is there in the film. I hope they really enjoy the music and let it loose with the music. I think it is also an amazing perspective on today. You know 1972 and 2024 had a lot of parallels politically. It is quite amazing and refreshing to step away from now for 90 minutes and go to 1972 and I think it helps get a perspective on now.”