FOREVER CHANGES – 50 YEARS LATER

It’s fair to say that Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the album that defined the Summer of Love, and the whole spirit of pop music in 1967. It dripped of lush psychedelia, baroque pop and Indian raga. But following that fateful summer, another album was released that reflected a darker, more realistic side to the new movement that was at its peak: Love’s Forever Changes.

Arthur Lee was born in Memphis, but from the age of seven onward lived in Los Angeles. This move would prove to be an act of fate as he ended up two doors down from future band mate and fellow Memphian, guitarist Johnny Echols. The two hit it off right away and formed a friendship that would last for years.

“One day we were having show and tell in school,” said Johnny Echols in the documentary Love Story. “There was this kid named Danny Oaken, and he brought a guitar to class. For some reason, he had to go to the nurses’ office and he asked me to take care of the guitar. It was just electrifying, just the feeling of the guitar. It just tickles your soul.”

Several years later, Echols was playing guitar in front of his high school in their gym. Not only did this impress all the girls at the school, according to Echols, but Arthur Lee, then a basketball star, also took a great interest too. Lee joined Echols group playing bongo drums but soon switched over to keyboards. The group, soon to be called the American Four, would play anything from weddings to funerals to bar mitzvahs playing alongside of future stars Billy Preston and Jimi Hendrix. During this time, Echols and Lee were signed as session musicians to the small California label Del-Fi, best known for being the label of Ritchie Valens.

During their hectic schedule, Echols and Lee became acquainted with Byrds roadie Bryan MacLean, who also happened to be a guitarist. Following the Byrds’ successful 1965 tour, the band stayed over in England to hang with the Beatles. MacLean decided to return to Los Angeles. He auditioned for Echols and Lee, and within a week they had formed a new group. Originally naming the band the Grass Roots, they soon found out the name had been taken by another folk-rock band. It’s difficult to say which band formed first, but the situation had irritated front man Arthur Lee. However, he decided to dismiss his feelings of resentment and opted to call the band Love.

Soon the band would recruit drummer Don Conka and former Surfaris’ bassist, Ken Forssi. Love began playing in local L.A. dives before becoming the house band in the small club, Bido Lidos, where they honed their material seven nights a week.

“My very first experience of Love was when I stumbled into a club called Bido Lidos,” said John Densemore of the Doors. “Here was this group, and they were deafeningly loud; and they were mixed racially. My mind was blown, to use the ‘60s term.”

The racial aspect of the group, a very important piece to Love, cannot be understated. To have an interracial group in the midst of the race riots all over America, but especially in L.A. where Compton saw the brunt of demonstrations, was a true inspiration and clearly showed the band was appropriately titled. “We were the best band in Hollywood,” said Arthur Lee in the 2006 documentary Love Story. “I had the first integrated rock group. I mean, as good as the Beatles — they were four white boys.”

By late 1965, Hollywood was the place to be making music. The Byrds had put the City of Angels on the map musically the previous year. A scene began to form that included Buffalo Springfield, the Mothers, and of course, Love. The dynamic mixture of folk-rock and early psychedelic music began to reflect the beginnings of a social revolution that started in California. The new movement, which reflected a more liberal philosophy, began to seep its way into the rock scene, both in a musical sense and in a fashion sense. Arthur Lee adopted a trippier way of dressing, predating Hendrix as the first psychedelic black man in rock.

By the time Love had become a local smash, drummer Don Conka had developed a serious drug problem that began weighing the band down. The group made the decision to replace him with the straight-edge Alban “Snoopy” Pfisterer. Lee would write the moving “Signed D.C.” about Conka’s heroin addiction.

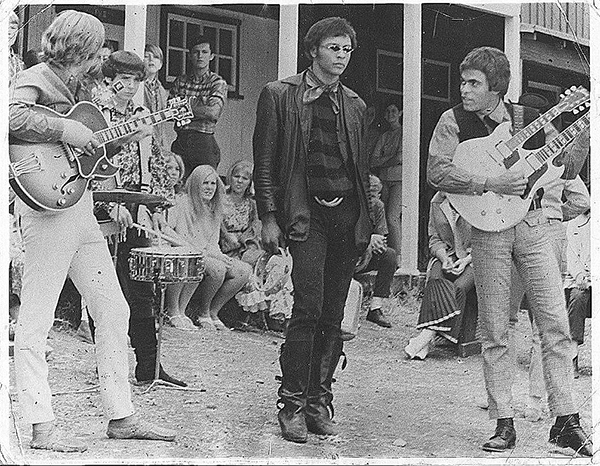

Love (Left to right – Bryan MacLean, “Snoopy” Pfisterer, Arthur Lee, Johnny Echols) performing in 1966.

In early 1966, the group was approached by Elektra Records founder, Jac Holzman. Holzman started the company 16 years prior as an independent folk outlet. However, after signing the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 1965, he began searching for more electric artists to gather for his hip label.

Love wasted no time after signing their record deal and recorded their self-titled album with producer Bruce Botnik at the legendary Sunset Sound recording studios. The album was essentially a setlist of one their Bido Lidos shows, made up of jangly folk and hard-edged proto-punk. The album’s first single “My Little Red Book”, originally a ballad written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, was rearranged by the group in a power pop style which earned Love a spot on American Bandstand.

In August 1966 the band scored another minor hit with the punky-psych tune “7 & 7 Is”, which charted at number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100.

For their second recording endeavour, Love decided to get a little more experimental by adding baroque elements to their proto-punk sound. The baroque revival was relatively new in 1966, used most notably by the Beach Boys on Pet Sounds. The 19-minute “Revelation” and the waltz-time album opener, “Stephanie Knows Who”, sound like Bach on an acid trip. The album featured Love newcomers Tjay Cantrelli on sax and flute and Michael Stuart on drums, which gave their regular percussionist, “Snoopy” Pfisterer, the chance to rip on the harpsichord and organ. Love hooked up with future Doors producer Paul Rothchild, and recorded a seven-song psychedelic gem. The album, Da Capo, was released in November 1966. Despite being one of the best recordings of the year, it failed again to capture an audience for the radical band.

Part of the reason for their lack of success came down to something very simple — race. Many clubs who had booked Love cancelled their gigs after they found out they were an interracial band. So for the time being, the band toured mostly in Los Angeles where they were accepted by the burgeoning scene in West Hollywood. The band’s communal home, The Castle, had become a local hangout for fellow musicians like Janis Joplin and the Jefferson Airplane who would flop there when they were in town. For over a year the group lived together in their villa, divulging in debaucherous orgies and indoor roller-skating. It was incredibly ‘60s.

After the completion of Da Capo, Love wasted no time, and began working on new material. With Cantrelli and Pfisterer’s departure from the group, this made way for a stripped down, rustic feel. Echols, Lee and MacLean, at the suggestion of Elektra founder Jac Holzman, dug out their acoustics and began composing folk tunes for what was to be Forever Changes. Brought in early on in the project to co-produce with Bruce Botnik was the young Buffalo Springfield member, Neil Young. Although he contributed to the arrangement of “The Daily Planet”, Young excused himself from the project and began pursuing a solo career. It is debatable whether he stole the title “Old Man” from Love’s Forever Changes or not.

“It was meant to be a two-album set,” Echols later said. “We wanted to have an opportunity to kind of showcase ourselves (referring to himself and Bryan MacLean) more. With a two-album set Bryan and I would get to do seven or eight songs, Arthur would do his amount, and we’d consider it our magnum opus.”

Despite Love’s attempt at making their first double-album, Elektra reneged, saying that it would be too expensive to produce. Elektra’s choice to cheap out on Love’s next recording endeavor would have a serious effect on the bands chemistry. Only two of MacLean’s tracks would be included on the final album, and none of Echols. MacLean’s resentment for their front man became intense, and he stopped putting in effort to play on Lee’s tracks during the early sessions.

“I’ve seen bands who are totally democratic and make it work,” said Holzman. “They make it work because everybody in that band is as smart as everybody else. It was true of Queen, it was true of the Doors. It wasn’t the case of Love.”

Due to McClean’s lack of effort, Botnik was forced to bring members of Phil Spector’s legendary “Wrecking Crew” in to play instead of the regular band members, who would instead dub small parts over after the song was finished. Botnik felt that this would inspire the fellow members of Love seeing their songs being played by outsiders, which of course it did, and the band came back to play on the rest of the sessions. “So, everybody just kind of got together and talked, and decided that we’re just going to finish this album,” Echols said. “Jac (Holzman) came in with some incentives, he offered us a lot more money. We got back into the studio and within a week or two we had finished. But it had taken months and we were getting nowhere and on the verge of walking away then.”

Despite McClean and Echols not getting the second disc added to the album that they had hoped for, their marks in the grooves cannot be overlooked. The opening bars of flamenco guitar on Bryan McClean’s song “Alone Again Or”, played by Echols, kickstarts the album, and has since become the most well-known track on Forever Changes. The Spanish-Mariachi feel heard on the song, seeps into some of the Forever Changes tunes, including the guitar solo heard on “A House is Not a Motel” and the brilliant trumpet parts on “Maybe the People Would be the Times or Between Clark and Hilldale”.

Lee in 1967.

After the songs had been laid out, Lee felt something was missing. The stunning lyrics and gorgeous acoustic melodies were not enough to satisfy his constant perfectionism. Both Botnik and Lee thought it could use an orchestral arrangement, so the two brought in composer/session musician David Angel.

Apart from the unique folk arrangements that was noticeably different from Forever Changes, the album’s deeply poetic lyrical offerings reflect a more realistic view of the counterculture and the times in general. “A House is Not a Motel” shows a satirical view of the hippies positivity while “The Red Telephone” refers to the Washington-Moscow hotline set up in the ‘60s. MacLean’s “Old Man” should not be overlooked either as he sees a reflection of himself in an old man he encounters, which inspires him to fall in love to find fulfillment in his life, which is just getting started. But it is the closing song, “You Set the Scene” written by Lee, that is the most impressive song, both musically and lyrically on Forever Changes. The song, which reflects the view of existence through the eyes of someone on an LSD trip, takes the listener on a deeply emotional ride for nearly seven minutes. Lee, who had been taking copious amounts of acid, was convinced that his life was near an end. This inspired his carpe diem-like lyrics in the album’s closer as he felt this was the last song he would ever sing. “This is the time and life that I am living/And I’ll face each day with a smile/For the time and life that I’ve been given is such a little while/And the things that I must do consist of more than style” sings Lee, inspiring the listener to make their short life matter. He continues with the evocative question: “To everyone that thinks life is just a game/Do you like the part you’re playing?”. Another thing that set Lee’s verse apart from others’, was his revolting against the typical verse-chorus-verse structure in pop. His lyrics have little structure on these tracks, but a profound impact. It wouldn’t be a stretch to call his verse early rap.

Lee and Angel spent three weeks going over the arrangements before recording the overdubs in one session in September 1967.

The title for the album, one of the most memorable in rock history, actually sprung from a breakup conversation between Arthur Lee and a girlfriend at the time. The conversation was overheard by some of the fellow Love members, including Echols and McClean. Legend has it his girlfriend pleaded with Lee saying, “You told me you’d love me forever”. Lee responded: “Well, forever changes”.

Billboard promotion for “Forever Changes” in Los Angeles, 1967.

Forever Changes was released November 1, 1967. In the face of the musical brilliance laden in the disc, it was not a commercial success. It spent 10 weeks in the charts, peaking at 154 in early 1968. In the U.K. however, Forever Changes gained a much stronger following peaking at number 24 on their album charts. Part of the reason for its lack of success was Elektra’s promotion of the Doors, whom Love helped get signed to their label the previous year. The Doors, who had several mainstream hits by the fall of 1967, were now Elektra’s main priority. Another contributing factor to the band’s commercial failure was Arthur Lee, who refused to tour anywhere outside of Los Angeles.

Following the release of the album, MacLean approached Lee asking his approval for his planned solo record. Lee congratulated him and fired him immediately. He later dismissed all the other members in 1968 when their drug abuse became too much. He reformed the group immediately with Jay Donnellan (guitar), Frank Fayad (bass) and George Suranovich (guitar). Four Sail, released in 1969, saw the new rendition of Love delve into Hendrix-like rock. The album, which is a strong effort, failed to capture the greatness of their previous recordings in particular, Forever Changes.

Lee kept Love alive for the next 25 years, going through various lineup changes, until he was sentenced to jail in 1996 on gun charges. After his release in 2001, he was back at it, performing again with another new lineup of Love, which briefly including Johnny Echols. This rendition of the group can be heard on the 2003 live album, The Forever Changes Live Concert, the last album released by Love.

Arthur Lee died in August 2006 after battling leukemia. Love was officially dead. Three years later Echols started a Love tribute band called Love Revisited. The band still tour today.

“Forever Changes” album cover. The faces of the band members were painted in the shape of a heart.

In the years following the release of Love’s masterpiece, Forever Changes, it has gained an immense cult following and is nearly always listed among the greatest albums ever recorded. In 2003 Rolling Stone ranked it at 40 on their list of 500 Greatest Albums of All-time while Mojo readers ranked it at 11 in their “100 Greatest Albums Ever Made” in 1996. The album has also been praised by artists like Robert Plant and the Stone Roses. The latter cite it as their favourite album.

Forever Changes, perhaps more than any album released in 1967 stands out for it’s overtly separation from the hippy culture. Tracks like “Maybe the People Would be the Times or Between Clark and Hilldale” and “The Good Humor Man He Sees Everything Like This”, show Lee’s pessimistic view of the Summer of Love which had just come to an end. Lee wanted to have a sense of reality conveyed in his music, which Forever Changes most certainly has. Singing about the inevitability of death, the Cold War and race relations were done in quiet protest, wrapped up in a mosaic of acoustic guitars and baroque and Spanish instrumentation.